Text and language have functioned as central artistic materials in postwar and contemporary art, fundamentally altering how meaning, authorship, and interpretation are understood. Rather than serving as explanatory supplements to images, words are frequently deployed as autonomous forms, structural devices, or conceptual frameworks.

From the mid-twentieth century onward, artists increasingly recognized language as a system that shapes perception, authority, and knowledge. By foregrounding text, artists redirected attention from visual representation toward questions of meaning, context, and power.

Historical Foundations

The use of language as an artistic material has roots in early twentieth-century avant-garde practices. Dada and Surrealism introduced strategies that destabilized meaning through wordplay, chance, and linguistic disruption, questioning the stability of representation itself.

These developments were later reinforced by philosophy and linguistics, particularly structuralism and analytic philosophy, which emphasized language as a rule-based system rather than a transparent vehicle for expression.

The emergence of Conceptual Art in the 1960s marked a decisive shift, positioning language at the center of artistic practice and enabling artists to prioritize ideas, definitions, and propositions over visual form.

Language as Artistic Material

In text-based practices, language operates as material rather than message. Words appear as isolated statements, lists, definitions, instructions, or typographic arrangements, often detached from narrative or illustrative context.

Joseph Kosuth articulated this position explicitly, arguing that art exists as an analytic proposition rather than a visual phenomenon. His work foregrounded language as both subject and medium, positioning definition and meaning as the core of artistic inquiry.

Meaning emerges through syntax, placement, repetition, and scale. The act of reading becomes integral to the work, positioning the viewer as an active participant rather than a passive observer.

Text, Image, and Cultural Language

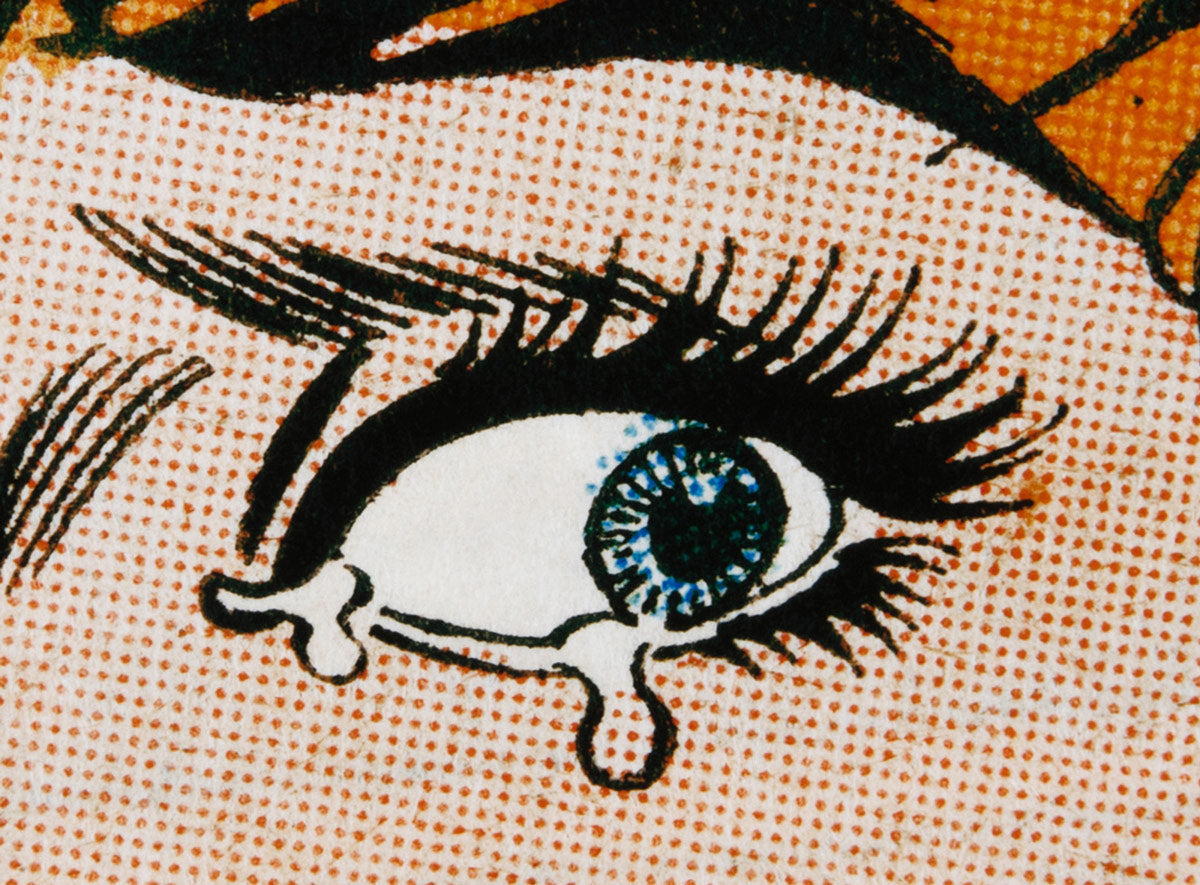

Language-based practices frequently intersect with visual culture, advertising, and mass communication. Rather than operating in isolation, text is often paired with photographic or graphic imagery to expose the mechanics of persuasion and representation.

Ed Ruscha occupies a pivotal position in this context, using words, signage, and typographic forms to examine language as a visual and cultural system. His work bridges Conceptual Art and Pop Art, emphasizing repetition, neutrality, and the material presence of words.

By isolating familiar phrases and formats, artists reveal how language structures expectation and meaning.

Power, Ideology, and Public Address

Text-based art frequently operates as direct address, particularly within public space. Statements placed on walls, billboards, posters, or projections confront viewers outside traditional institutional settings.

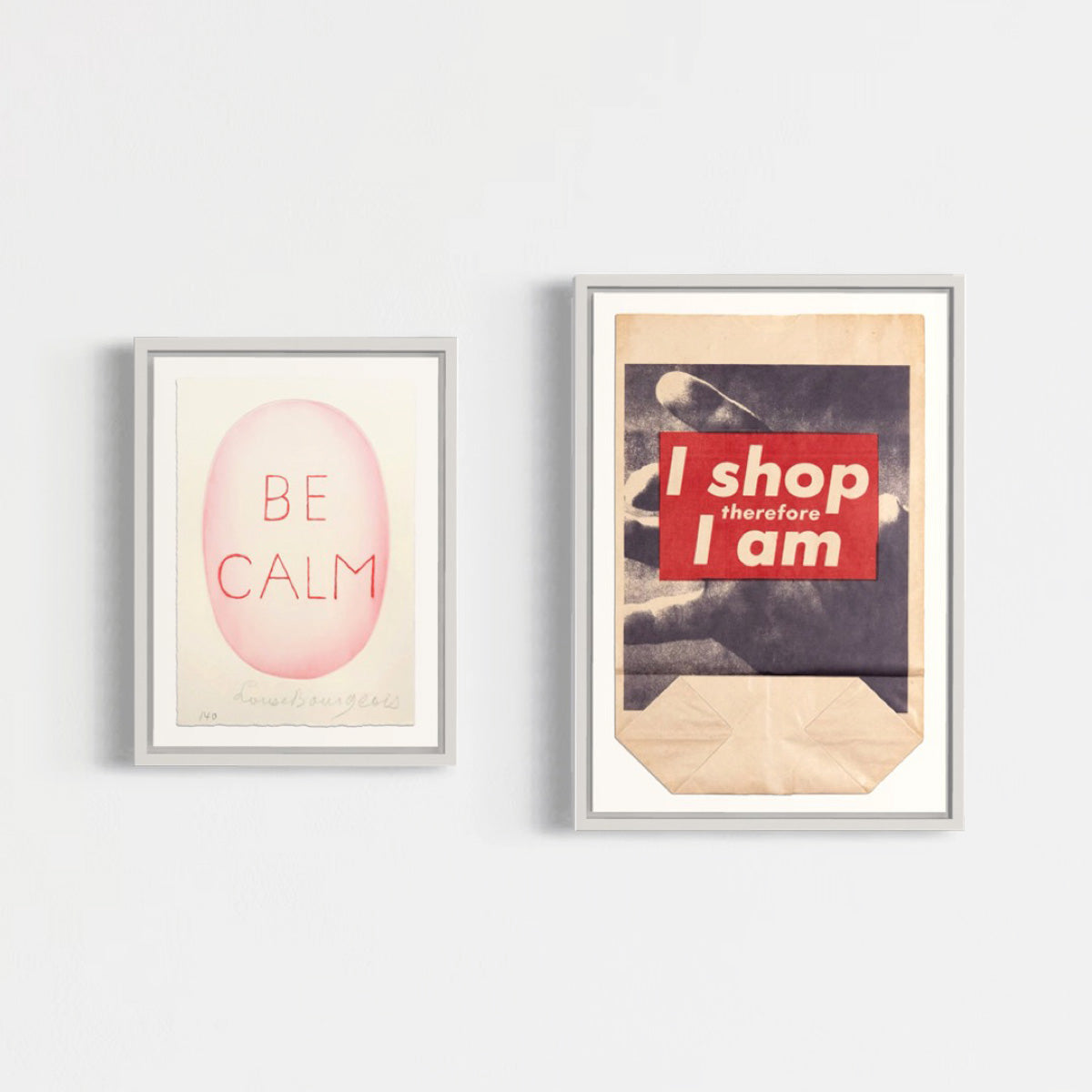

Barbara Kruger exemplifies this approach through the use of declarative language combined with graphic design strategies borrowed from advertising and mass media. Her work exposes the ideological power embedded in everyday language, addressing issues of identity, authority, and consumption.

By adopting familiar visual formats, such practices collapse distinctions between art, information, and propaganda, revealing how language operates within systems of power.

Reproducibility and Circulation

Text-based works are inherently suited to reproduction and circulation. Language can be printed, projected, translated, and disseminated across multiple contexts without losing its structural integrity.

This reproducibility challenges traditional hierarchies of originality and uniqueness, aligning text-based practices with editions, multiples, and distributed formats.

As a result, language-based art has played a significant role in reshaping how artworks circulate within institutions, publications, and the market.

Contemporary Practice and Relevance

In contemporary art, text remains a vital tool for addressing questions of identity, politics, and representation. Artists continue to explore how meaning shifts through repetition, humor, ambiguity, and narrative disruption.

Laure Prouvost employs language in combination with video and installation to construct fragmented narratives that blur fiction and instruction, destabilizing authority and comprehension.

David Shrigley uses text and drawing to expose the absurdity of everyday language, transforming banal or instructional phrases into sites of humor, discomfort, and reflection.

In an era defined by accelerated communication and image saturation, language remains a potent artistic tool for examining how meaning is produced, distorted, and controlled.

Editorial Note

This editorial page examines the role of text and language as artistic materials, tracing their historical foundations, conceptual strategies, and continued relevance within contemporary art.