Pop Art emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s as a critical response to mass culture, consumerism, and the expanding influence of media imagery. Drawing on advertising, popular entertainment, commercial design, and everyday objects, Pop Art challenged traditional distinctions between high art and popular culture.

Rather than rejecting the visual language of mass production, Pop artists embraced it, using familiar images and materials to reflect on contemporary life. The movement redefined subject matter, authorship, and originality, positioning art within the visual economy of modern consumer society.

Origins and Cultural Context

Pop Art developed almost simultaneously in the United Kingdom and the United States, shaped by postwar economic growth, the rise of television, and the proliferation of advertising imagery. Artists responded to a rapidly changing visual environment in which images circulated with unprecedented speed and volume.

In contrast to the introspection of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art adopted an outward-looking perspective. It foregrounded the shared visual language of everyday life, transforming commercial imagery into a site of artistic inquiry.

The movement questioned traditional ideas of artistic originality, instead engaging with repetition, appropriation, and mechanical reproduction.

Image, Language, and Appropriation

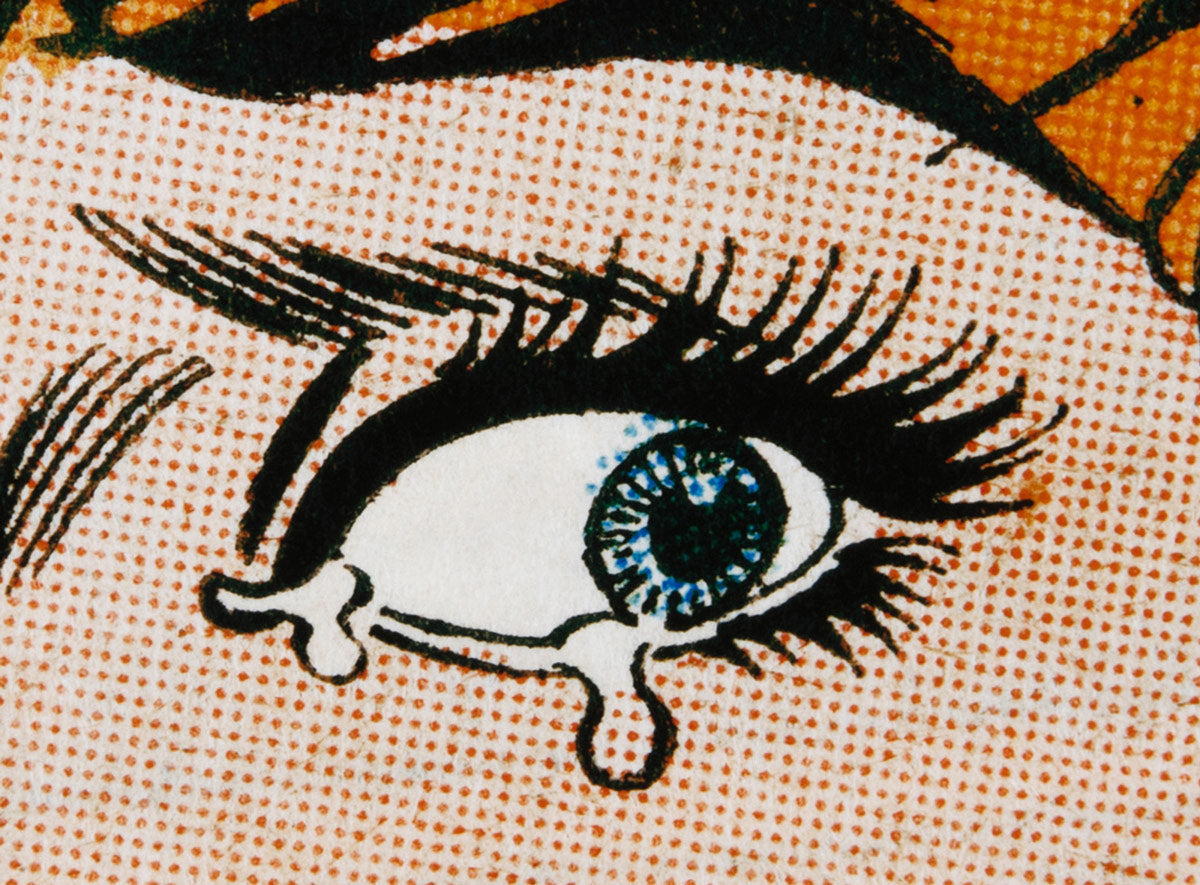

Pop Art frequently employs strategies of appropriation, isolating and recontextualizing images drawn from advertising, comics, film, and print media. By removing these images from their original commercial contexts, artists exposed the mechanisms through which meaning and desire are constructed.

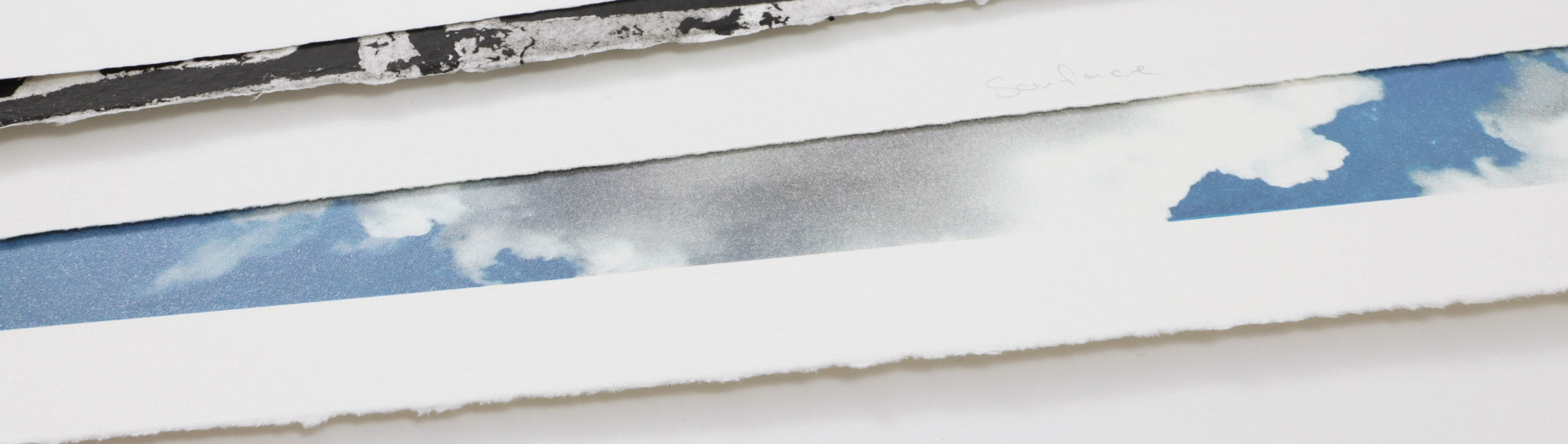

Ed Ruscha occupies a pivotal position within this discourse, using language, signage, and typography as primary visual material. His work bridges Pop Art and Conceptual Art, foregrounding the relationship between words, images, and cultural expectation.

Text and image function not as narrative devices, but as objects in their own right, emphasizing surface, repetition, and visual immediacy.

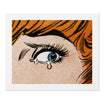

Painting and the Pop Image

Painting remained a central medium within Pop Art, though it was redefined through flat color, sharp contours, and photographic reference. Pop painters rejected expressive brushwork in favor of clarity, legibility, and visual impact.

Alex Katz developed a distinctive approach that combined large-scale figurative imagery with reductive composition. His work engages popular aesthetics while maintaining a rigorous formal discipline, positioning him at the intersection of Pop Art and postwar abstraction.

Pop painting emphasized immediacy and recognition, inviting viewers to confront images already embedded in collective visual memory.

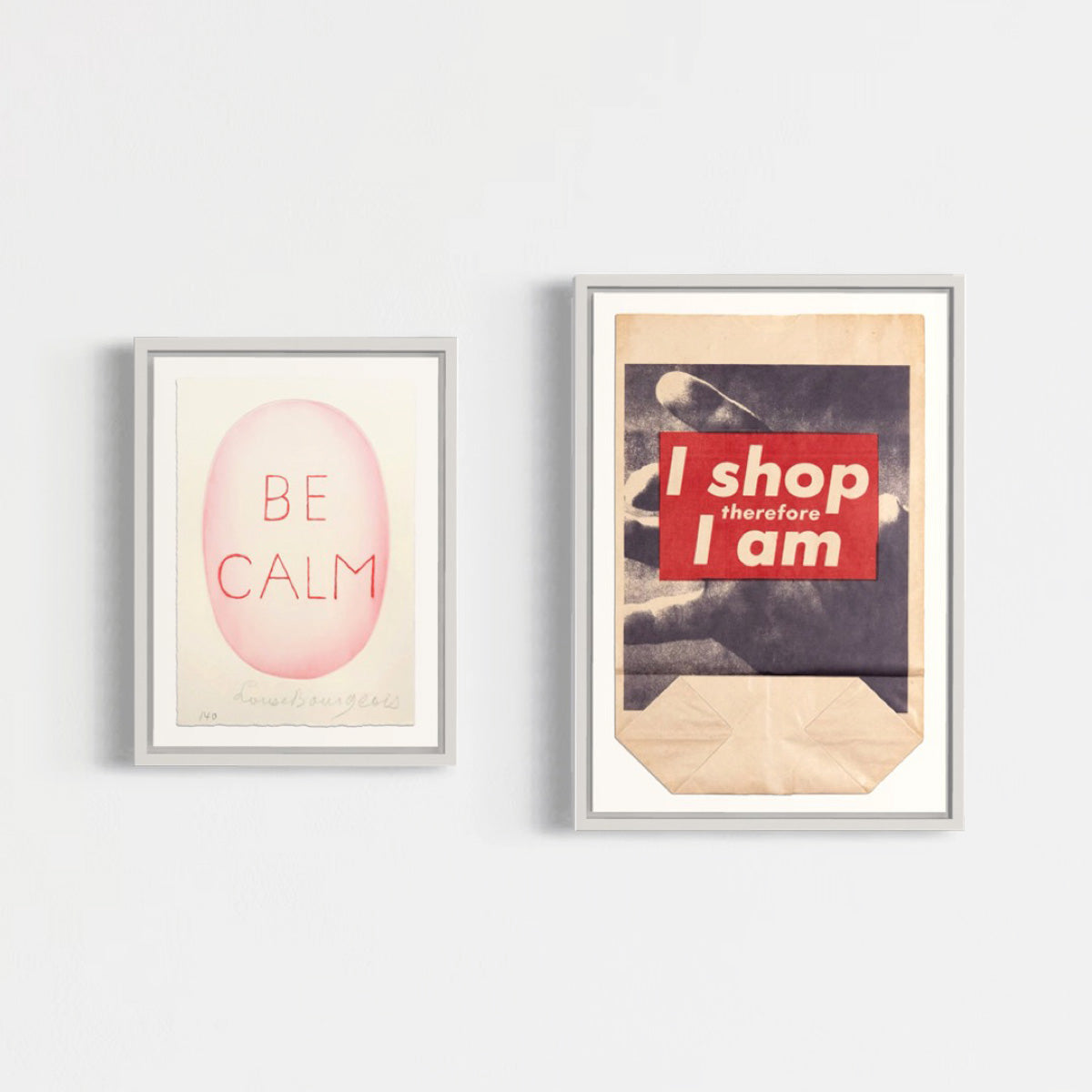

Desire, Consumption, and the Body

Pop Art frequently addresses themes of desire, consumption, and spectacle, reflecting the commodification of images and bodies within mass media. Advertising imagery and idealized figures become tools for examining cultural norms and visual pleasure.

Mel Ramos explored these themes through figurative compositions that reference pin-up imagery and commercial illustration. His work highlights the intersection of consumer culture, fantasy, and representation.

By amplifying and exaggerating these visual codes, Pop Art exposes the constructed nature of desire within consumer society.

Pop Art After Pop

The strategies introduced by Pop Art continue to shape contemporary artistic practice. Appropriation, repetition, and the use of existing images remain central to how artists engage with visual culture.

Richard Prince extends Pop Art’s legacy through practices that directly appropriate and reframe mass-media imagery, challenging notions of authorship and originality in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Pop Art’s influence is not confined to a historical moment, but persists as a method for critically engaging with contemporary image economies.

Pop Art and Contemporary Practice

Contemporary artists continue to draw on Pop Art’s visual language and conceptual strategies, adapting them to new cultural and technological contexts. Mass imagery, branding, and spectacle remain central concerns.

Damien Hirst engages Pop Art’s legacy through repetition, seriality, and the circulation of iconic motifs. His work reflects on value, belief, and commodification within the contemporary art market.

Through these extensions, Pop Art remains a living framework for understanding how images operate within contemporary culture.

Market and Institutional Reception

Pop Art achieved rapid institutional recognition and has since become a cornerstone of postwar art history. Major museum collections and exhibitions have established its lasting significance.

In the market, Pop Art is closely associated with editioned works, prints, and multiples, reflecting the movement’s engagement with reproducibility and mass circulation. These formats have played a key role in shaping collector engagement.

Pop Art continues to occupy a central position within both institutional and private collections worldwide.

Editorial Note

This editorial page provides an overview of Pop Art, tracing its origins, key characteristics, and lasting influence on contemporary art.

Selected works by artists associated with Pop Art are available through our collection.