Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art is an approach to artistic practice in which the idea, proposition, or system underlying a work takes precedence over its physical form. Emerging as a clearly articulated movement in the late 1960s, Conceptual Art redefined the role of the artwork, shifting emphasis away from visual appearance and material execution toward thought, language, and structure.

Rather than treating the art object as an end in itself, Conceptual Art positions it as a vehicle for ideas. In some cases, the object becomes secondary or unnecessary, replaced by instructions, texts, diagrams, or documentation. This shift marked a fundamental challenge to traditional assumptions about authorship, originality, and artistic value.

Origins and Early Influences

Although Conceptual Art emerged as a distinct movement in the second half of the twentieth century, its intellectual foundations extend back to the early avant-garde. Artists associated with Dada and Surrealism questioned the primacy of aesthetic form and introduced strategies that foregrounded intention, language, and conceptual framing.

Marcel Duchamp’s readymades established a decisive precedent by asserting that an ordinary object could become art through designation alone. This act displaced craftsmanship in favor of context and intention, laying the groundwork for later conceptual practices.

Surrealist artists expanded the role of ideas and language, while René Magritte’s investigations into the relationship between words and images directly anticipated later Conceptual concerns. His work exposed the instability of representation, a problem that would become central to Conceptual Art.

Historical Emergence

Conceptual Art took shape in the 1960s in response to the increasing formalism of postwar modernism and the growing commodification of art. Many artists sought alternatives to the expressive subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism and the object-centered rigor of Minimalism.

In this context, artists in the United States and Europe began to prioritize intellectual inquiry over visual resolution. Influenced by philosophy, linguistics, mathematics, and systems theory, they developed practices centered on rules, classifications, and propositions rather than expressive form.

Exhibitions, publications, and artist-run initiatives became crucial platforms for Conceptual Art, often proving more significant than the production of singular, autonomous objects.

Language, Text, and Meaning

Language occupies a central position within Conceptual Art, frequently functioning as the primary medium rather than a descriptive supplement. Text-based works explore how meaning is produced, constrained, and destabilized through linguistic structures.

Joseph Kosuth articulated this position explicitly, arguing that art exists as an analytic proposition rather than a visual phenomenon. His work foregrounded definitions, statements, and philosophical inquiry, positioning language as both subject and material.

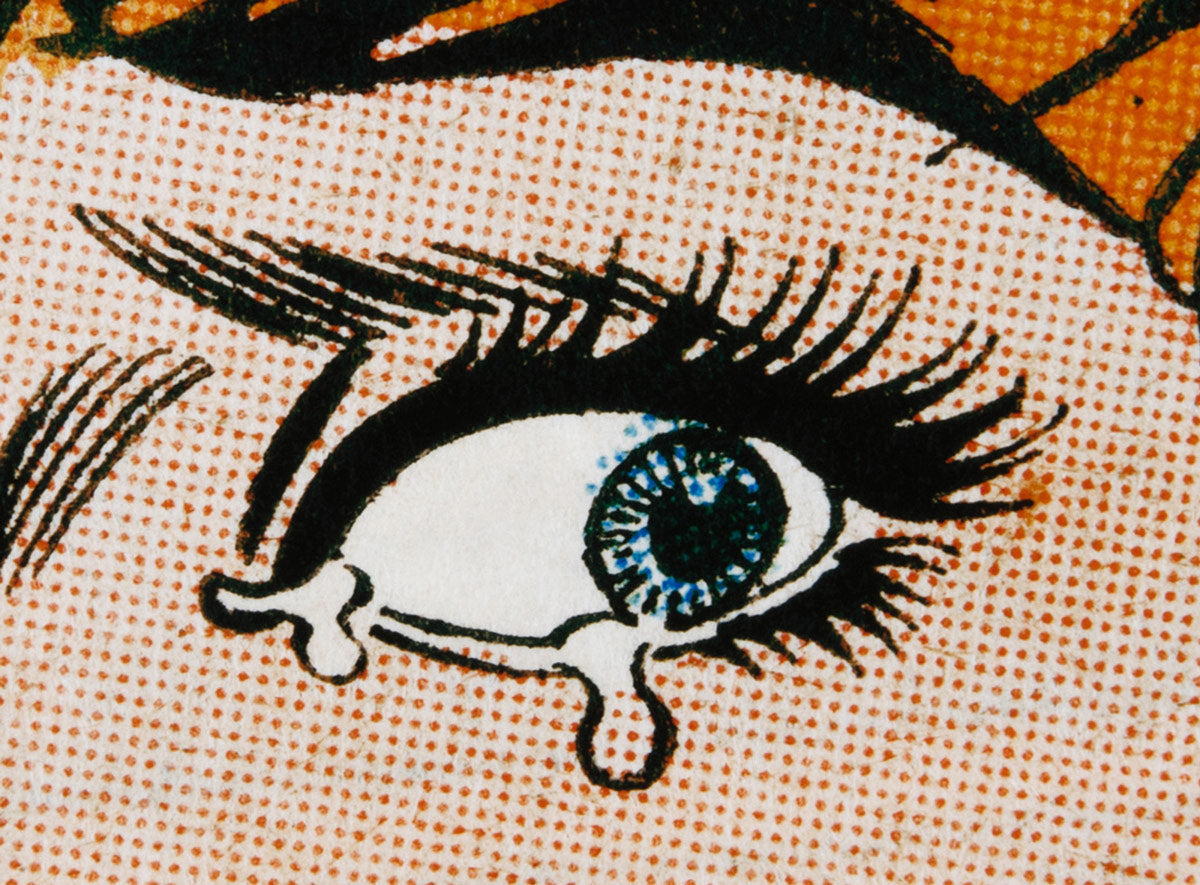

Similarly, Ed Ruscha employed text and serial imagery to examine systems of representation, repetition, and cultural language. His books, photographs, and word-based works bridged Conceptual Art and Pop sensibilities, emphasizing structure over expression.

In the United States, John Baldessari played a decisive role in translating Conceptual strategies into image-based practice. By combining text, found imagery, and instructional logic, Baldessari challenged conventions of authorship and visual meaning while maintaining Conceptual Art’s emphasis on ideas over aesthetic resolution.

Systems and Seriality

Many Conceptual artists adopted systems and serial structures to reduce subjective decision-making. By establishing predetermined rules, artists could explore variation, repetition, and difference without relying on personal expression.

This emphasis on structure positioned artworks as investigations rather than aesthetic conclusions. The work often unfolded over time or across multiple iterations, reinforcing the idea that meaning accumulates through process rather than visual impact.

Sol LeWitt articulated this logic with particular clarity, defining Conceptual Art as a practice in which “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” His wall drawings and structures exemplify how predetermined systems can generate form without expressive intervention, positioning execution as a neutral, rule-based process.

Authorship and Execution

Conceptual Art fundamentally redefined authorship by separating conception from execution. Instructions could be realized by others, delegated, or remain unrealized without compromising the identity of the work.

This approach questioned long-standing assumptions about originality and authenticity. If a work can be repeatedly executed according to a set of conditions, its essence resides in the idea rather than the material result.

This separation between conception and realization became foundational for later practices, with LeWitt’s instructional works serving as a model for how authorship could persist independently of physical production.

Documentation, certificates, and diagrams often became the primary means through which works were preserved and transmitted, reinforcing the immaterial nature of Conceptual practice.

Market and Circulation

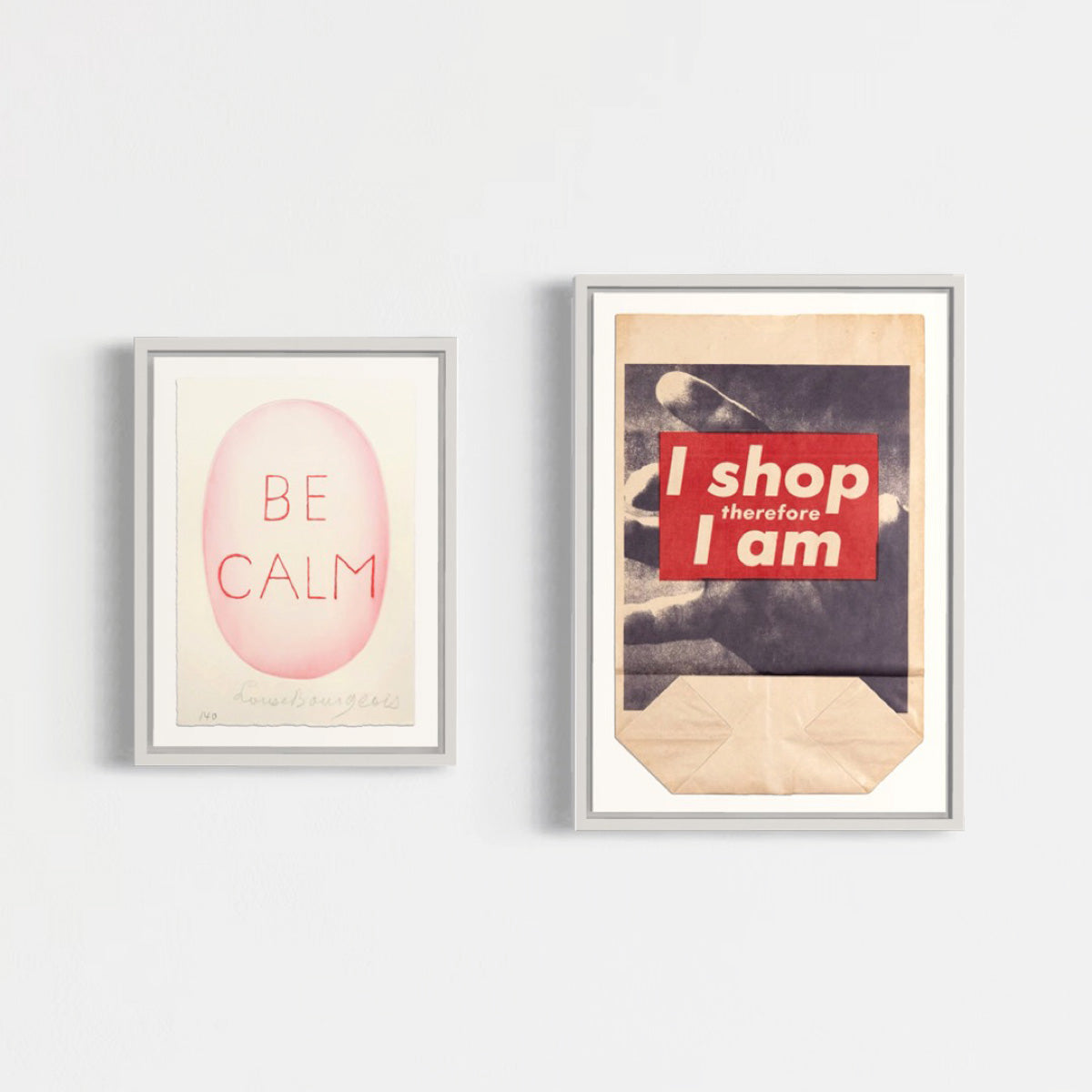

Although initially positioned as a critique of commodification, Conceptual Art ultimately transformed the art market rather than existing outside it. New forms of collectibility emerged, including editioned texts, photographic documentation, diagrams, and authorized instructions.

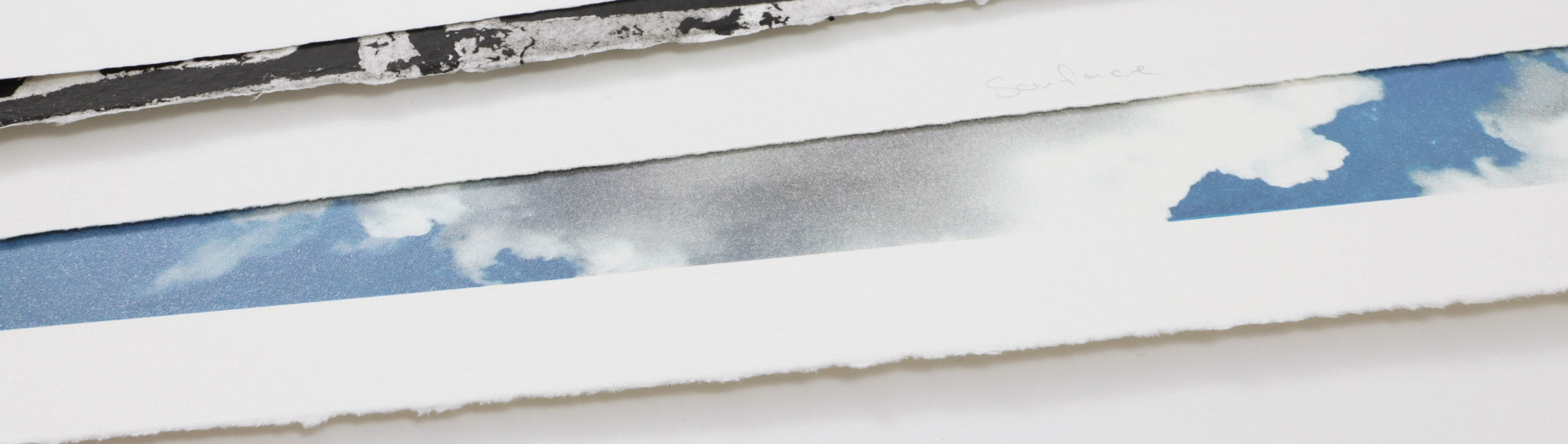

Prints and multiples played a particularly important role, allowing Conceptual works to circulate while maintaining intellectual rigor. These formats enabled broader dissemination and introduced alternative models of ownership grounded in authorization rather than material singularity.

Today, Conceptual Art occupies a central position within museum collections and the secondary market, reflecting its lasting influence on how art is produced, distributed, and valued.

Legacy and Contemporary Practice

The impact of Conceptual Art extends well beyond its historical moment. Its strategies underpin a wide range of contemporary practices, including installation, performance, institutional critique, and theoretically informed painting.

Artists such as Peter Halley exemplify how Conceptual Art’s emphasis on systems and theory continued to shape later practices. Drawing on systems theory, architecture, and social structures, Halley translated Conceptual logic into a diagrammatic painterly language, demonstrating how ideas rooted in Conceptual Art could be rearticulated through visual form.

Later generations of artists have continued to engage with Conceptual frameworks, applying systems-based thinking and analytical structures to new visual and social contexts. In this sense, Conceptual Art functions not as a closed historical movement, but as an enduring methodological foundation.

By foregrounding ideas, context, and structure, Conceptual Art remains a vital reference point for understanding contemporary art today.

Editorial Note

This editorial page provides an overview of Conceptual Art, tracing its origins, key ideas, and lasting influence on contemporary practice. Particular attention is given to language, systems, and the redefinition of authorship.

Selected works by artists associated with Conceptual Art are available through our collection.